Maximal Aerobic Speed (MAS Training)

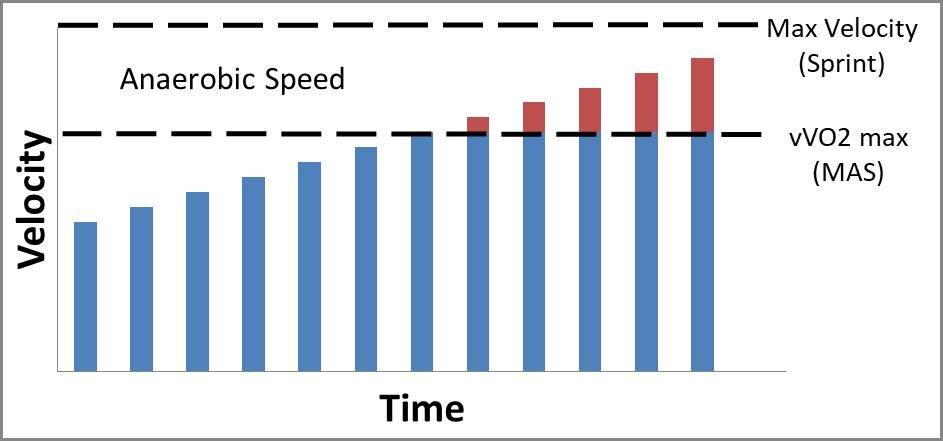

Maximal aerobic speed (MAS) is a term used to describe the lowest running speed at which VO2 max occurs (maximum oxygen uptake). It can also be known as the velocity at VO2 max (vVO2 max). Athletes can run faster and continue working despite reaching VO2 max; MAS is simply the slowest speed an athlete will reach maximum oxygen uptake. Figure 1 below might give you a clearer understanding of what MAS is.

Figure 1. Figure shows a VO2 max test. MAS is the slowest running speed at which maximum oxygen uptake (VO2max) occurs. The line at “vVO2max” is the velocity at which VO2max occurs, but as you can see one’s running speed can go well above this level. So an athlete can continue to run, even run faster, despite already hitting VO2 max. Other energy systems (Anaerobic and ATP-PC systems) are used to reach speeds closer to Max Velocity as simply inhaling oxygen isn’t effective at hitting those energy demands.

MAS training has become enormously popular in recent years, expanding its usage from elite squads to amateur teams. The need and want to improve players aerobic power is a highly sought after feature and can often be the critical for success in team field-based sports[1]. These improved performances however are usually in the form of increased distance covered, higher work intensity and a greater number of sprints performed[2].

Research into aerobic training

Most research looking into aerobic training is now focused on Maximal Aerobic Speed (MAS). The research clearly shows that the key to improving aerobic power is the amount of time spent above your MAS (Maximal Aerobic Speed: slowest running speed at which VO2 max occurs). So running at 120% of your MAS is more effective then running at 100% of your MAS. If an athletes MAS is 4.6 meters/second (m/s), running efforts at 5.52m/s (120% MAS) will improve aerobic power at a greater rate.

Training that involves performing short intervals at speeds greater than 100% MAS is highly effective and, to be more specific, intensities of 120% MAS [3]. This was in comparison to long slow distance training (LSD) and running continuously at 100% MAS. So going out and getting in your 5k run on the roads might not be the most effective strategy you can do to improve your aerobic power for the field.

Intervals at 90, 100 and 140% MAS didn’t provide the same impulse or the appropriate combination of intensity and volume to get the same effects as 120% MAS. This involves intervals of 15-30 seconds followed by an equal amount of rest between reps and repeated for 5-10 minutes.

So, in summary, high intensity intervals of 15-30 seconds, with similar rest times (either passive rest or low intensity activity e.g. 40-70% MAS), continued for 5-10 minutes and repeated for a number of sets, usually 2-4, will improve aerobic power and work capacity.

Testing for MAS

To accurately measure MAS, you’ll need to book a session with your local physiologist or sport scientist. Hop on the treadmill in the lab, wearing head and mouth pieces that are hooked up to a machine that provides gas analysis. With that said, it may not be the best route to go. Running speeds will tend to differ between the treadmill and the sports field.

Test where you’ll train! A running-based field test is always the simplest option and is as effective as the lab testing. There has been a number of varied tests developed that correlate with MAS – the Montreal Beep test, the YoYo IR1, time trials of 5-7 minutes, or have a set distance that will take athletes between 5-7 minutes to complete (e.g. 1200m).

I won’t get into how to conduct each test, but it’s important to know how to determine MAS from each test before you begin as some test results will require using equations (e.g. Multistage Shuttle Beep Test).

Once athletes have been tested, it’s best to express MAS as meters/sec (m/s). This can be very easy to do for the likes of a set distance test. For instance, a 1500m time trial takes an athlete 5 minutes to complete. 5 minutes is equal to 300 seconds, 1500m divided by 300 seconds, that’s a MAS of 5m/s.

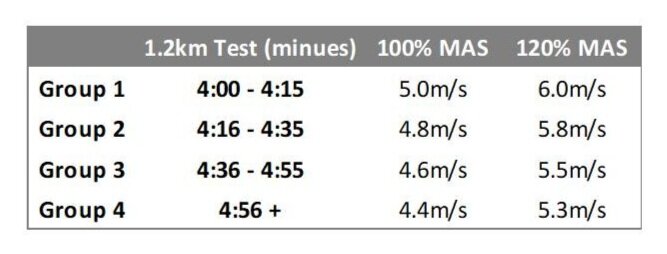

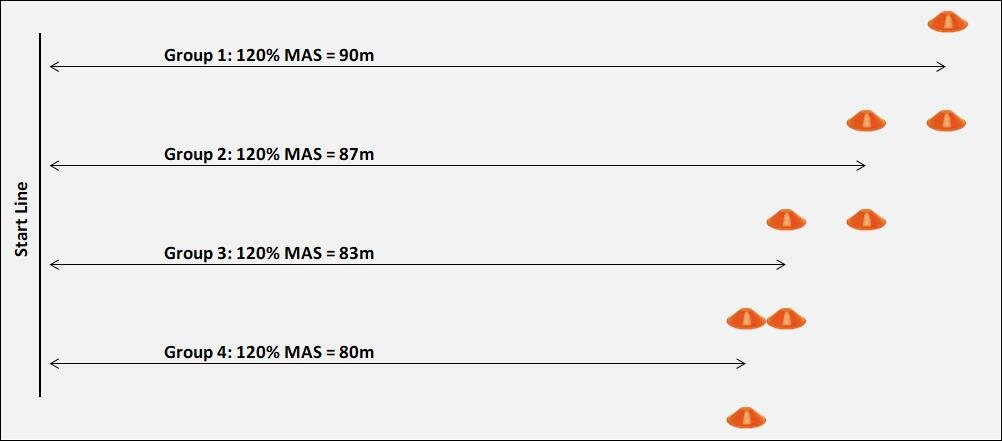

Table 1. From MAS test results, athletes can then be assigned into groups based on their test results. From this, each group will perform varying distances depending on their own ability. (The data from the table below is not accurate, has been manipulated to make it easier to read and should not be used for your athletes).

Training with MAS

There are a number of different methods that can be used for high-intensity aerobic training using MAS results, Long Intervals, Grids Method, Eurofit Method, Tabata Method and the Unpredictable Tabata. All of these, if structured correctly, can yield good results.

Long Intervals

Like most training programs, intensities should start low and is turned up over time. Long intervals could provide “base” training, for want of a better phrase. Intervals of 60 seconds up to 5 minutes are generally used at intensities between 85-100% MAS. Longer intervals are best suited for early on in your preparation phase before adding in higher intensity work. Those with both poor MAS scores and/or aerobic development will benefit more from this training.

Performing reps using long intervals should be thought through. Based on your time trial, your athlete may have been able to sustain their 100% MAS pace for, let’s say, 5 minutes. That’s a maximum effort test, so prescribing multiple reps of 3 minutes intervals at 100% MAS will be extremely difficult, if not impossible. So here’s the key – the longer the interval, the lower the intensity.

Work: Rest ratios range from 1:1 to 3:2, but rest ratio can be decreased further if the % MAS is less the 90%.

A typical session may look something like:

2 sets of 5 x 2 minute intervals at 95% MAS with 2 minute rest

Grids Method

Or the “100% MAS:70% MAS Method”. This is a continuous method that uses active recovery. These use short intervals of 15-30 seconds at 100-110% MAS with 15-30 seconds of active recovery at 50-70% MAS. This is then continued for 5-10 minutes.

The term grids is based on the pitch set-up, a series of concentric rectangular grids with the dimensions matching each groups required distances to run; the slowest group on the smallest inside rectangle and the fastest group working around the largest outside grid.

Figure 1. An example of the Grids setup with concentric rectangles, 100% MAS on the long sides and 70% on the short sides.

The above figure is a sample session where athletes run each side of the grid in 15 seconds, running the longer sides at a quicker speed then the smaller sides. Group 1 runs 75m while Group 4 runs 66m on the long sides at 100% MAS, and 53m and 46m respectfully on the short sides at 70% MAS. Everyone is working at their own MAS capabilities. This way, each of the groups hit each corner at the same time and all complete a lap around the grid in 1 minute. Typically, start off with 5 minutes for 2-4 sets and build up to 6, 7 or 8 minutes depending on your sport’s requirements and its aerobic demands. I would advise to build up the number of sets rather than go hit 8 minutes.

Tips: If you have a large squad you can separate them further just by MAS score; spread them to start at the opposite corners. Make sure athletes stay disciplined on the short sides and not to run quicker than 70%, otherwise the session will turn anaerobic. So to keep the pace, I use a whistle every 15 seconds to indicate to the athletes the point when they should be at the corner. With all training sessions you should plan ahead, make sure you have an area large enough to conduct the Grids. Very fit athletes running for 30 seconds at 100% MAS may hit 150m – that’s a big grid!

Eurofit Method

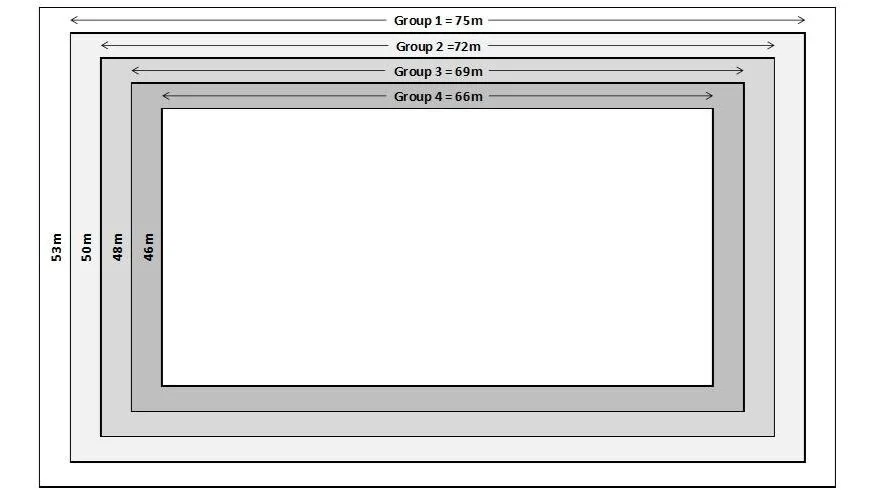

This is the most popular method of MAS training because of its simplicity. Run out your distance in the time, wait at the end for usually the same time, and then run back, repeated and repeated. Traditionally the Eurofit Method works at 120% MAS and 1:1 work to rest ratio; 15 seconds on, 15 seconds off. Like the Grids Method, initially work for 5 minutes and building up to 8-10 minutes, again depending on the demands of your sport, and performing only 1-2 sets. I suggest building the athletes work capacity for a few weeks before increasing the intensity, which can go up to 125 and 130% MAS respectfully.

Set up is individualised to each group, faster groups run further as seen in the Figure below (Figure 2). For example, everyone has 15 seconds to run to their respective distance, 15 seconds rest, and return back to the start line in 15 seconds, rest 15 seconds again and the process keeps repeating for the duration you’ve set, usually 6-10 minutes.

Figure 2. An example of the Eurofit Method. 1:1 Work:Rest Ratio of 15 second intervals. Staggered lanes means each group works at their appropriate intensity.

Tabata Method

Modified from its original exhausting protocol to more appropriate intensities for field sports, the Tabata Method is quite similar to the Eurofit Method in its field setup. The difference being the work:rest ratio; Eurofit uses 1:1 while the Tabata uses 2:1 (20 seconds on, 10 seconds off). Not as exhausting as its original protocol, but very challenging nonetheless, performed at around 120% MAS.

Unpredictable Tabata

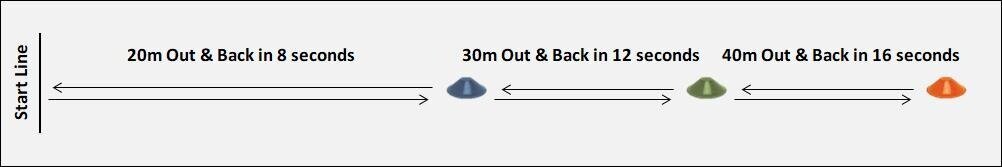

This variation maintains a 2:1 work:rest ratio but the length of the interval is varied every rep. There will be multiple distance options that athletes run depending on the decision of the coach. Set up at three interval lengths, example, 20m out, 30m out and 40m out from the start line. Once the rep begins, wait a couple seconds and then give the command which of the designated cones they must reach and return back to the start line from in said time: 8 seconds for the 20m out and back, 12 seconds for the 30 m out and back and 16 seconds for the 40m out and back. These out and back variations can also be used in the regular Tabata Method. Turning and changing direction is quite taxing on the body and is thought to increase the anaerobic energy contribution [4]. Something to take note of when considering what your goal for the session is.

Figure 3. Tabata (Out and Back). The turn adds an anaerobic element to the training so this should be more fatiguing then linear efforts.

Figure 4. Unpredictable Tabata. Various coloured markers for each distance. Give the command of which marker to go to a couple seconds after they leave the start line.

Programming MAS

To me, MAS should only be implemented in the Preparation Phase of training and shouldn’t be used in season during competition. Firstly, MAS is extremely fatiguing so it may affect player’s recovery between games, second, during the season I think your better to spend time maintaining your fitness levels using Small Sided Games, saves time and you kill two birds with one stone. Personally I think that any high-intensity days during the competition phase should focus on speed rather than high intensity aerobic training.

Programming MAS into your Preparation Phase is easily progressed, and you can follow the various MAS methods in the order they were listed in as an appropriate intensity progression. If you start at a high intensity where do you go from there? Start low and build up. Depending on how long your Pre-season is will dictate how long you spend with each MAS cycle.

Progressing the intensity is easy – simply following the systematic use of all the varied MAS methods listed above will naturally do this. Starting with Long Intervals (85-100% MAS), then the Grids (100% MAS), on to the Eurofit Method (120% MAS), and perhaps going higher again and using Tabata and Unpredictable Tabata. Using each method for 1-3 week cycles, again depending how much time you have to prepare.

Within each cycle the volume should progressed appropriately to the player’s abilities and the sports demands. There will be a marked decrease in volume when you switch from one method to another but this can be used as a de-load week, to ensure over-training is avoided. Yes there will be a reduction in volume once you enter a new cycle but the new MAS method will be working at a higher intensity.

Personal Thoughts

There is no doubt that MAS improves your field tests and other fitness markers, there is however a concern that MAS doesn’t improve Repeated Sprint Ability which is essentially what most field sports require – Be fast, and do it often. There is also questions and philosophical issues surrounding MAS, like how to implement MAS alongside Speed Training? That yes, it is high intensity efforts, but in yet the running speeds are slow.

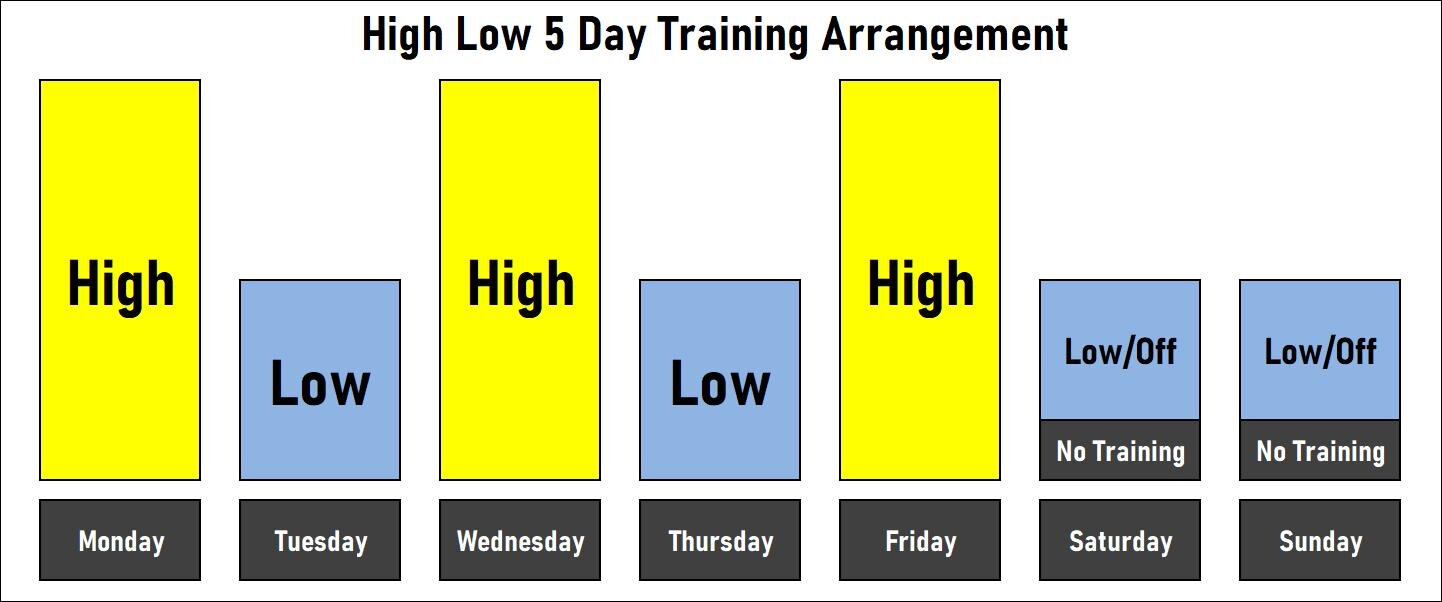

Personally I wouldn’t rely on MAS solely. Blending it in with Tempos may be more appropriate (click here to learn more about Tempo Runs), and to use it very early on in the preparation phase. For me, I think training Speed is a crucial part of athletic development which requires plenty of recovery and depending on what your training philosophy is will dictate if you implement MAS into your system. For me, I follow the High-Low training model (Figure 5.). This model focuses on the training effect on the Central Nervous System (CNS), simply that High Intensity is very fatiguing to the CNS, while low intensity is not, the first requires a lot of recovery, 48-72 hours, while the later usually 24 hours (sometimes more). Does it fit within the High-Low training model? It can, if you implement a lot of low intensity skill development and tactical learning drills as Low days. So High days could be either Speed or MAS focused.

Table 2. Sample of activities that fall into the categories of High and Low Intensity.

Figure 5. Example of a 5 day arrangement using the High-Low Model. High Intensity days are 48 hours apart to ensure adequate recovery. Low Intensity days can be completed between high Intensity days as they will have very little impact to recovery.

For most field based team sports, speed wins. And the objective as a strength and conditioning coach should be to program the highest possible intensity efforts, repeated with the greatest frequency possible. I’m paraphrasing Mladen Jovanovic, a quote I heard a while back but one that stuck with me. To but it simply, players should sprint and train to be able to sprint often. “But aren’t we talking aerobic conditioning?”- Yes we are. But you need to understand the bigger picture and not just one aspect of training.

MAS is quite slow. Performing at the highest efforts of 130% MAS doesn’t come close to sprinting speed. As we are not developing max outputs with MAS, we train at submax efforts that usually push athletes above their lactate threshold. Coaches reading this might be smiling and saying to themselves that that’s exactly what they want to see, players gritting their teeth and very fatigued, that must mean players are getting fitter, right?

Although having a high lactate tolerance is a great asset, this type of training will not be optimal to develop the aerobic system. During a game we don’t want players using the anaerobic system too regularly as its high fatiguing thus affecting match performance. So to avoid dipping into this system, it’s important to have a well-developed aerobic system. The bigger your aerobic capacity, the higher your lactate threshold and so too improves your ability to maintain high power outputs for longer. The added bonus is that a well-developed aerobic system improves recovery time between repeated high intensity efforts (improving you repeated sprint ability).

The best aerobic athletes in the world would do very little of MAS type efforts (low volume of medium-high intensity work). A huge volume of their training is low intensity, a portion of high intensity, and in competition preparation phases of training they would start doing some lactate tolerance sessions. If the fittest athletes in the world only use a MAS style of training coming up to competitions and not to improve their aerobic system, why do coaches use high intensity MAS as in their foundation during pre-season? So if you are using MAS, don’t skip phases to do more intense workouts! Start low and build-up slowly. I see so many teams beginning their season running at 120% MAS and never build that “base” fitness.

So when done appropriately MAS will improve your players fitness levels, but at the expense of other high intensity workouts. From Table 2 you can see that MAS is under High Intensity because of its high fatigue factor, but is really a medium-high intensity activity. Last time I checked, the High-Low Model doesn’t fit a medium day in it. Performing MAS on High Intensity day’s means that we have to sacrifice other high intensity activities.

“So what, I’ll just have the players sprint, do game practise and MAS at the end?” You can do this, but you shouldn’t. High Intensity Aerobic training paired with speed or strength training causes an interference affect. Often gains in one will be compromised by the other as your body is trying to adapt to two very different stimuli.

Performing MAS on Low Intensity Days will affect recovery from High Intensity days. Your body won’t be fully recovered to perform high intensity work as it takes longer than 24 hours to recover from MAS.

The reason strength and conditioning coaches exist is because it was found out that playing the sport is an inefficient stimulus for adaptation. You must then do two things; Train at intensities higher than the sport and train at intensities lower than the sport. Think about your sport for a second, more specifically the intensity is it easy or is it hard? Most field sports GAA, Soccer, Rugby, are not a walk in the park, but they are not maximal either, they’re somewhere in the middle. So if we train in this middle zone do we improve? (Clue: reread this paragraph). The answer, inefficiently.

Maximal Aerobic Speed would also fall into this middle zone. If match play/small sided games and MAS all land in the same middle intensity zone and that playing the sport is inefficient for physiological development, how are we going to improve performance?

Perhaps we should leave middle zone to Small Sided Games and game practise.

How would I implement MAS?

I have used MAS in the past and to a large degree but have transitioned to using Tempo runs more regularly. Using athletes MAS is a system I like, individualised and often suitable for most players. Players who are on the unfit side don’t feel like they’re chasing to keep up with the bunch, everyone simply runs their own pace. Using the Long Intervals is a good place to start your season, lower intensity then your typical MAS runs, develops aerobic system well and can fit in the High-Low training Model, just gives players that base fitness aerobic conditioning with low impact running.

Using Grids would be as far as I go when using MAS, still relatively low intensity but working on aerobic capacity. I would use players RPE to also gauge the session, looking for about 4-6 to ensure they’re not working too hard and make the workout more anaerobic.

Eurofit, Tabata and any other high intensity variation would not be used. I would leave any sort of lactate tolerance drills to small sided games, best bang for your buck. Remember that at the end of the day, players play a skill based sport so any chance you have to add a ball into the mixed is best for everyone. If there are attendance issues and players can’t make training sessions that you had planned to work on a lot of high intensity games, you could simply get those players to do MAS runs instead, wherever they may be. Use MAS to mimic small sided games that were scheduled for that day of training.

I hope from this write up that you haven’t been discouraged from using MAS, but a better understanding of another means of conditioning. When it comes to conditioning athletes, often there is no wrong or right way to do it. What’s usually wrong or right is when you do it. This come down to time of year, phase of training and even assessing needs on weekly bases.

References

[1] Baker, D. & N. Heaney. Some Normative Data for Maximal Aerobic Speed for Field Sport Athletes: A Brief Review. Journal of Australian Strength & Conditioning (in review).

[2] Helgerud, J., Engen, L.C., Wisloff, U., & Hoff, J. Aerobic endurance training improves soccer performance. Med Sci Sports Exercise. 33:1925-1931, 2001.

[3] Dupont, G., N. Blondel, G. Lensel, and S. Berthoin. Critical velocity and time spent at a high level of O2 for short intermittent runs at supramaximal velocities. Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology. 27:103–115. 2002.

[4] Buchheit, M. The 30-15 Intermittent Fitness Test: Accuracy for individualizing interval training of young intermittent sport players. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 22(2):365-374. 2008.